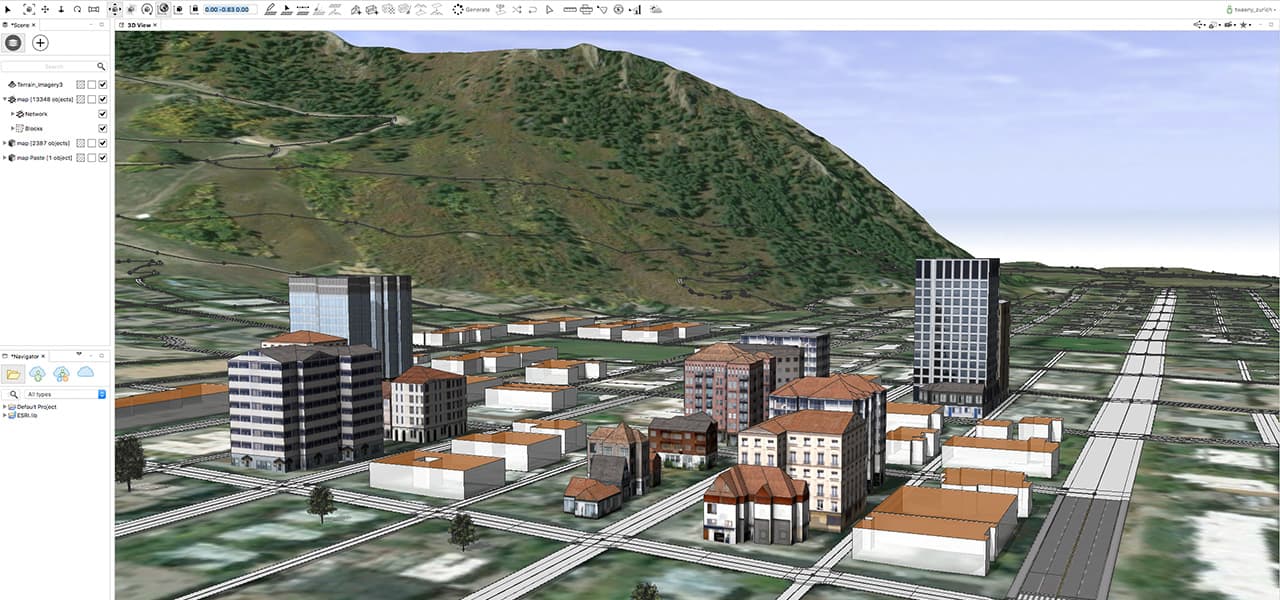

CityEngine is like… well, it’s a lot like SketchUp on steroids. Those familiar with generative components, or that design-school-darling Rhino and its Grasshopper plugin, already understand procedural generation.ĮSRI’s CityEngine uniquely enables procedural generation for city-scale content creation. Whenever a player moves to the edges of the ‘known world’, more terrain is procedurally generated. MineCraft makes extensive use of procedural generation. However, procedural generation has recently made a big comeback in a new class of voxel-based terrain games called ‘sand-box modelers’.

Today, games ship with tons of ‘dead parrots’ (polygons) and handmade 3D Art. Regrettably, capacious memory has since largely obviated such programmatic cleverness. This content strategy was called procedural generation, whereby needed virtual real-estate gets whipped up procedurally ‘just-in-time’ from rule-based algorithms. This forced content such as maps to be generated algorithmically on-the-fly – there simply wasn’t enough space to store large amounts of pre-made levels and 2D/3D Art. The result was a unique user experience I call ‘structured play’, that proved to be an addictive approach to 3D content creation (we’ll come back to this).Įarly video games similarly had severe memory limitations. SketchUp’s inference engine gave users an intuitive pen and paper like “drawing” experience paired with simple tools that let designers play with their designs in a way that had not been done before. The severe limitations of viewing 3D objects on a 2D screen forced Joe Esch to invent the geometric inference engine in the late 90’s, and SketchUp was born.

Not surprising then, forced compromise also drives the very best software design. Then as professional designers, we routinely seek the deepest design constraints early to begin negotiating the forced compromise of good design. In school, young architects quickly learn that severe constraints are often their best friend.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)